postmaster@museumofanthropocenetechnology.org

via Leggiuno 32

2014 Laveno Mombello

Italia

How I talk(ed) about climate change

(Excerpts of a presentation given for Next Generation Please! (BOZAR, Brussels, 19 Febr. 2021) The full presentation can be watched here.)

This is a presentation about climate change presentations.

The director of the Museum has given public lectures about climate change for the past 20 years. These lectures changed a lot during that period, because many things changed: the knowledge, the awareness, the political discourse and, last but not least, climate itself. Initially the lectures were rather scientific: explaining the physics of the greenhouse effect, how humans are enhancing it, etc.. Later on, they included more information on the problems that this might cause / is causing and what could be done about it: there was more about technology and economics and policy in the lectures. More recently, it become more about how to make people really aware of the problem. Lecture/performances were tried using theatrical elements to try and shake the audience. Eventually, it was more about understanding together, through dialogues, why it is difficult to make people, any people, react and do something. Then came COVID. Did this complicate the way one talks about climate change or did it help to go more at the bottom of what really causes our problems (see Cat. Nr. 91) ? The Museum settled on the need to go beyond our modern culture. But what does that exactly mean if one remains convinced that scientific research, the hallmark of our modern culture, will keep playing a fundamental role?

Here are some reflections by the director, shared with a young audience, on the various types of presentations. The hope is always that somebody in that audience, whether she wants to become a teacher, artist or engineer, might be interested in them, takes them over and starts building that new culture in which we can better tackle climate change and other collective problems.

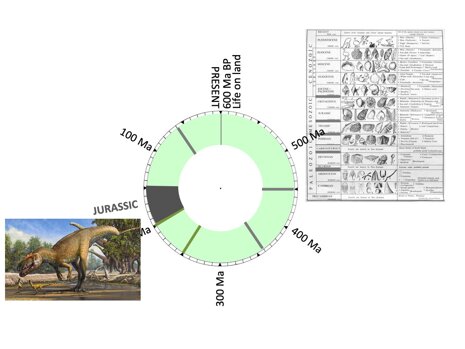

Presentation 1. A lecture / performance

that is about the history of the Earth, 4.5 billion years long, the various geological eras and epochs, the origin of Mankind and the Great Acceleration of the past 200 years announcing the Anthropocene. (see also

and

)

Reflection. It happened more than once that, after this presentation, somebody asked: “But why are you talking about all this? I came to hear about climate change and what can we do about it! I don’t care about mass extinctions and dinosaurs!”. The first answer is that it is a fascinating story! But what is even more fascinating is that we didn’t invent this story, but that it is the result of scientific research. Scientific research that allows us to get to know what previously we didn’t know. Scientific research which is making hypotheses of how things were and subsequently, through repeated observations, confirms (or rejects) these hypotheses. And in the case of confirmation, science doesn’t stop but continues and makes further observations, without ever being complacent, to get further confirmation. And as such, little by little science creates reality, in the sense that it creates solid knowledge about things that previously we didn’t know anything about. That is what science allows you to do. It is good to go through that long history of the Earth, first: because it puts the climate change that we witness today in perspective, but also because it might give you some confidence in what science is able to do. If we are able to say something coherent about the past 4,5 billion years, using science, we will also be able, using the same science, to say something about the next few hundred years, and about what climate change that we are witnessing today will bring.

But I accept that when you come to listen to a talk about climate change, this is not what you expect. And in the beginning, in 2014 when I started to use a first version the final sequence of slides (see Cat. Nr. XX and Trump was already a part of it!), I would kind of apologize to my public, saying that maybe I had exaggerated a bit. But as years passed by, I stopped apologizing because, at times, it seemed, to me at least, that the world had indeed entered an era of chaos.

It was als interesting to noticed how differently the public reacted to this sequence of slides. When I showed it to older people of my age, it often happened that there was a complete eerie silence after the final explosion. And it was difficult to figure out how they took it. Were they scared? Did I hurt their political feelings? Did they simply think I was making a fool of myself? On the contrary, when I showed it to a large audiences of school boys and girls, after the final explosion came a second explosion of applause and excitement.

You, the younger generation, see the world definitely very different than us, and, if you think about it, that is only normal. We have been giving public presentations about climate change for about 20 years, but 20 years ago you were not even born!. So you have been taking in climate change and other world problems with the milk bottle so to speak. That is very different for our generation, who 30 – 40 years ago didn’t have to bother about climate change and then, all of the sudden, we were exposed to it. It came for many people as something unbelievable and it disoriented them.

So, based on these reactions, I came to understand, that you youngsters find all these changes happening in society rather exciting and, actually, that can even be a reason for optimism.

Anyway, the main reason why I show this fast sequence of slides, after I went through the long and slow history of the Earth, is to show that things are going faster and faster, and that, seen on a geological time scale, we are really in the middle of an explosion. That is an objective reason of concern because nobody can say whether we have that explosion under control.

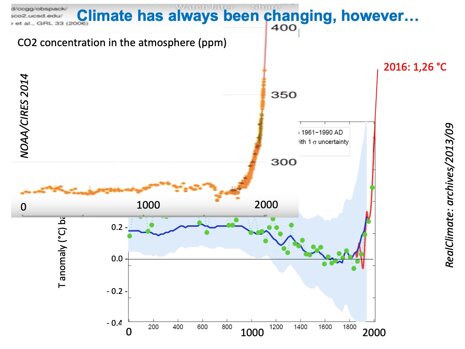

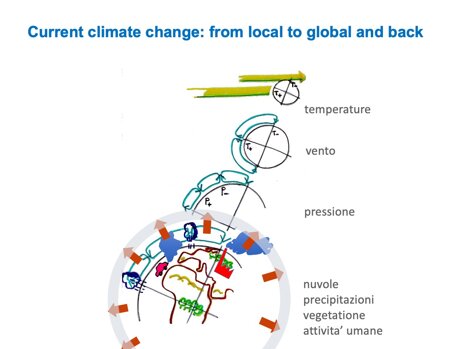

Presentation 2. Scientific data

show in a more sober way the rapid change in which we are in. By widening our perspective beyond that of a few generations, we see that the current global warming is something special. It also shows that it has a lot to do with the increase of CO2 and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, caused by human activities.

Through a cascade of processes, global warming transforms and manifests itself in local extreme events: heat waves but also cold spells, droughts but also floods. This leads already today to loss of life and economic damages. There is a limit to how much you can protect society from these losses, let alone adapt to them. To avoid the worst of climatic change, the emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases must be stopped.

Reflection. That all seems like a logical story. We actually also know how to reduce our emissions of greenhouse gases, So why don’t we just do it?

Many of us, scientists, learned the hard way that this is only a logical story for people with a scientific training, who can follow each step in the story and can be convinced about it. A couple of years ago I was giving a talk to professors of law. I showed the typical x-y plots that we scientists show. And I saw that hey could not understand: “Yes, it reminds me of high school”, somebody said. I had to drop all the slides I had prepared and entered in a dialogue with them.

There is really a need to talk about climate change in another way. Sometimes you are given 10 minutes to say something about climate change. So what do you say in 10 minutes? The interesting thing is that if you try another, more simple way, you also come to a different kind of conclusions.

Presentation 3. leads to the conclusion that climate change is an ethical problem.

Once you emit CO2 in the atmosphere, it will stay there for a very long time, up to a thousand years. As such they create a global and an intergenerational problem.

Reflection. I added the second slide to my presentations only two years ago, after a high school student asked me: “Why are you doing that: going around and giving these presentations?”. I knew why I was doing it, but I realized that I had never been explicit about it. Until 5 years ago, climate change was a rather rational issue for me. I told the logical Al Gore kind of story: there is a problem, we have solutions, so let’s do it. Then I started to realize that the scientific rational approach is not the only game in town. I myself started to care more for other things. Undoubtedly, that happened because I retired. I retired early in order to have more time for other things. So, I consciously stepped out of my hectic life of managing a research group and dealing with colleagues in Brussels, etc., and yes, nearly automatically I found time to deal and care for other things. I started to think about my children and children in general and the future we would leave them behind. I started to care more about nature itself. I had an emotional encounter with … a glacier. It was, I felt, like a dying whale, laying on the bottom of the valley. It felt not right. Also, the many pictures of people in the poor side of the world who see their livelihoods destroyed because of the way we live in the rich part of the world: is this fair?

There is another thing. Going through all that, I also learned that it is important to make explicit why you are doing what you are doing, and why you are saying what you are saying. Share these personal thoughts. If you give a talk to a public, you can feel when there is full attention in the room: you hear a kind of silence which is special. And I can tell you that such a silence does not fall when you explain the greenhouse effect, but it always does when you tell something about yourself. That tells that the people in the audience are all sitting there with their own personal thoughts and feelings and that they are continuously confronting them with the ideas of the one that is talking on the stage. It tells that we cannot talk only about the climate outside us, but that we also have to dare to talk about the climate inside us.

“For there will always be light, if only we dare to see it, if only we dare to be it.” (Amanda Gorman). Beautiful words but quite a challenge also for me

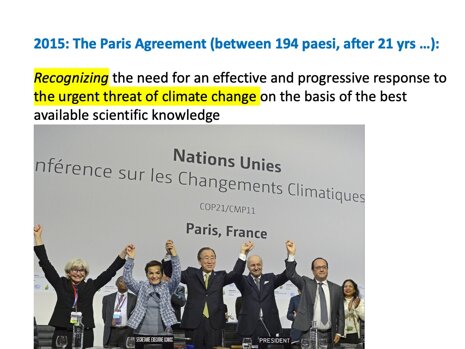

Presentation 4. Back to hard reality: politics and action.

Parallel, but not always in tune with the science, a political mechanism had started under the leadership of the United Nations, which, in 2015 after 21 years of negotiations, lead to the Paris Accord. All countries agreed to “hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre- industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre- industrial levels.”

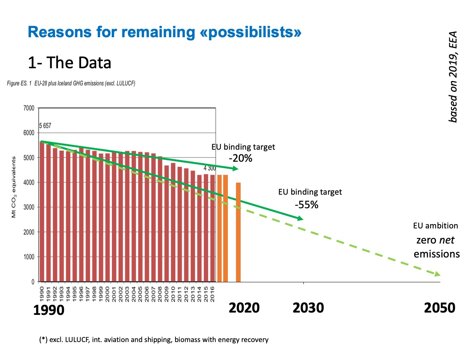

Limiting warming to 1,5 degrees means ZERO-ing the net global emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050. In the European Union greenhouse gas emissions have been going down since 1990, while GDP has been increasing. The emissions in 2020 will be about 30% lower than in 1990.

Reflection. Is this giving an optimistic or pessimistic picture? In giving climate talks it has always been an issue whether we should scare people so that they start acting. Greta Thunberg, for instance, clearly showed her concern about her future and was mad at my generation that we didn’t seem to care. On the other hand, we also know that if you scare people too much with problems that are too big, they will switch off. According to psychologists, that is in fact a very human reaction: “cognitive dissonance”, they call it. So, most communicators would argue that we must present as-much-as-possible (!) a positive picture: I would call it a possibilistic picture.

Presentation 5. Reasons to remain possibilistic.

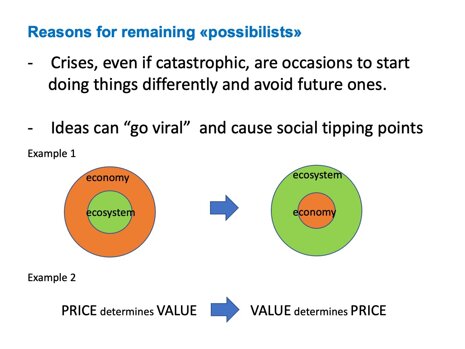

It is true that the EU reduced its emissions also (!) because of a number of dramatic unpredictable events. But unpredictable events always do occur and they will also occur in the next 30 years, simply because society, including humans and non-humans, is a complex system. They can include further jumps in awareness, the going viral of relevant new (or old) ideas, and technological breakthroughs. As a society, we try to avoid catastrophic events, but if they occur, we need to see also the opportunities to improve, so that the pain is not in vain.

Reflection. There is one last thing I want to tell you, namely that you are my favorite audience, and a final reason why we can remain possibilist, is in fact YOU.

You are still in high school and you need to decide soon what to study or what to make of your life. Well, it doesn’t matter what job you will do, as we said before, there is work for everybody, it is more important howyou do it and that you do it with some sense of responsibility towards other people and the rest of Nature.

And you should realize that you are very well prepared for this. You have been growing up with the climate change issue, biodiversity loss, etc. So you somehow understand them better than the older generation: yours is not a rational understanding but it is an integral part of yourself. You also have been hearing about new technologies, smart technologies, renewable energies etc., all of your life, which makes you better prepared to tackle any problem. I am kind of convinced that you are going to tackle a problem like climate change. You might want to tackle it for very different personal reasons: you might feel deeply concerned about our Planet Earth and everything it hosts, or you might be appalled by the injustice that goes with climate change, or you might realize that reducing car use will also bring you cleaner air, will give more space to nature, will give more time for yourself. You might even see business opportunities in all this. So there is no way I can think that you are not going to manage this. Let me repeat this without using a double negative: I can only think that you are going to manage this, for the betterment of yourself, the people around you and the rest of Nature.

postmaster@museumofanthropocenetechnology.org, via Leggiuno 32

Laveno Mombello

21014

Italia